It’s a decade since artist and facilitator Lesley Cherry’s gilt-framed artwork, made up of hundreds of photographs taken by Shankill residents, was unveiled on the side of a house on Hopewell Crescent, once a popular site for the area’s infamous Loyalist murals. Commissioned by the Lower Shankill Community Association, it seemed the perfect embodiment of Cultural Democracy: the activist rallying cry represented by an artwork, campaigning for social change, a commentary both on the place and purpose of public art and of policy-led art programmes.

Resurgence

Not that anyone was talking about Cultural Democracy then. It was languishing in the closet of unfashionable cultural policy concepts, debated only by academics, policy-geeks and Eurocrats, and all but forgotten by practitioners. Recently, however, it has enjoyed a revival. It is galvanising practitioners, not just socially engaged artists but many of us working in mainstream cultural institutions.

As the debate around cultural value has warmed up, and the hard evidence that 20% of the population consume 80% of state supported culture has become harder to ignore, the success of people-centred organisations – like Fun Palaces, Creative People & Places, 64 Million Artists and Of/By/For in the US – in connecting far more inclusively has left a deep impression. They have taken up the flag of Cultural Democracy and a pragmatic view of it, less as a Utopian ideal forever confounded by the state and more as an achievable way of working. From Fun Palaces’ self-organising toolkit to 64 Million Artists’ Cultural Democracy In Practice, these organisations are finding ways to show how Cultural Democracy works – rather than debating if it can.

Benign influence or positive force?

As the appetite for more democratic and inclusive ways of working grows, is there a role for mainstream cultural institutions? My answer to this question is yes and no. There are major challenges for mainstream arts and cultural organisations to find a role in building cultural democracy but I would argue strongly that the effort is worth it. The effort may be the point.

Cultural Democracy proposes that the benefits of cultural and creative participation are distributed more widely, notions of cultural value are recognised more equitably, and decisions about the provision and resourcing of cultural opportunity are made democratically. It is, as Matarasso and Landry say, a policy or process for “increasing access to the means of cultural production, distribution and analysis”. It is sometimes defined in contrast to the ‘democratisation of culture’ - a top-down process where the ‘official’ culture is made accessible to non-participating communities, often in the belief that it will do them good.

It draws on concepts from the wider world of citizen participation and activism. In the United States in the 1960s Sherry Arnstein described citizen participation as “the redistribution of power that enables the have-not citizens, presently excluded from the political and economic processes, to be deliberately included in the future”. Her original (much adapted) ‘ladder of participation’ is still one useful way of defining what is and is not Cultural Democracy: only the Citizen Control mode would genuinely equate.

| 8. Citizen Control |

Citizen Control |

| 7. Delegation |

|

| 6. Partnership |

|

| 5. Placation |

Tokenism |

| 4. Consultation |

|

| 3. Informing |

|

| 2. Therapy |

Non-Participation |

| 1. Manipulation |

|

Most cultural organisations aim to be a benign influence in their community, and some explicitly to be a force for positive social change. Regardless of their aims, however, none are constituted as democracies and few are even set up to enable community decision-making in any material way. But this does not mean that their work is necessarily placating or tokenistic.

Step-by-step, paving the way

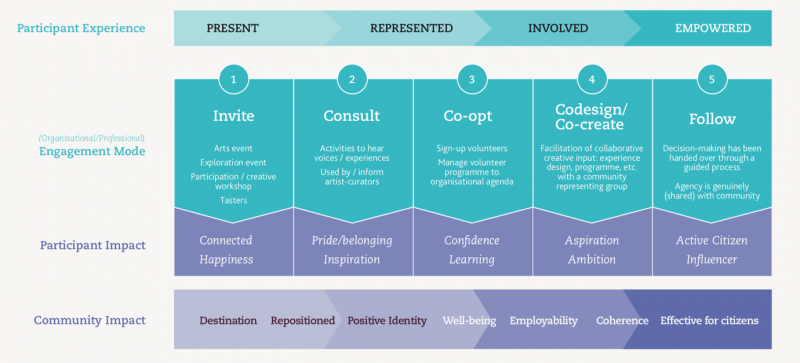

The Audience Agency’s Spectrum of Creative Participation, inspired by and based on evaluation with many community arts and cultural projects (including Creative People and Places in the UK) takes a view of Cultural Democracy from the perspective of a cultural organisation. It recognises the interventions of an organisation across a spectrum of modes, each of which could be relevant at different times and situations. This seems more pragmatic and helpful than a judgemental hierarchy which suggests that only the higher echelons of participation are legitimate. The intent and quality of execution of different modes of engagement can lend them integrity.

What we have observed is that organisations often need to move to and fro across this spectrum. As one practitioner told me, it is challenging to jump in at the deep end, without first developing the relevant skills and sensibilities you need, and without taking your community with you. 64 Million Artists advocate the higher ends of the spectrum but agree the value of incremental development: “Whilst true Cultural Democracy has a number of absolutes, the path towards it can be incremental and iterative. Not everything needs to be done at once.”

The Shared Decision-Making toolkit developed for Creative People and Places recommends that organisations considering shared decision-making should carefully consider what level of delegation is appropriate for them: “How will you make sure you are honest and upfront with everyone involved about where the ultimate decision-making will sit?”

The final “Follow” stage in the Spectrum clearly indicates the need for an institution or facilitator to step back, let go and support only when invited.

Distinctive Practice

Cultural Democracy then is not in the gift of most cultural institutions. At best, they might see it as the legacy of their work. Instead, we encourage cultural organisations to take active steps to working in a people-centred way. This is not some vague concept about being nice to people, but a distinctive set of practices, heavily informed by the disciplines of creative participation and community development. It is a recognisable approach used in the co-creation and delivery of both cultural and other public programmes and services aiming to create social value.

It is characterised by a common outlook towards:

- Process: distinctive approaches used to involve people and respond to their needs

- Power: concerted efforts to distribute power through shared decision-making, equitable allocation of resources and distributed leadership

- Principles: a way of working and acting based on mutual respect and social justice.

People-centred practice cannot be taught as such, but it can be learned and nurtured. Many of the people we have interviewed in our research advocate an experimental mindset and reflective practice. Institutions that are new to people-centred work cannot be expected to jump immediately to a radical decentralisation of power, but can start from an expert-led mode with the intention of moving - often iteratively and supportively - towards a more participatory and citizen-led future.

6 things your organisation can do to work more democratically

- Explore the use of ‘human-centred design’. This sets out many of the principles for excellent co-creation.

- Involve you community in material decision-making. Find a forum that works for you and make sure you can follow through.

- Iterate! Working closely with your community can be two steps forwards, one-step back. People need confidence, options and trust to be meaningful, and it will take time.

- Learn as you go. Foster a culture of experimentation. Only organisations that do this are able to adapt to emerging ideas and relationships.

- Explore the principles of Asset Based Community Development. This is a framework for equitable working preferred by many practitioners.

- Work with an expert facilitator. We may not give them due professional recognition, but we should! Working in this way requires know-how, sensitivity and passion.

This article first appeared in Arts Professional on 10th September 2020 as part of The Audience Agency's series sharing insights into the audiences for arts and culture.